I didn’t know Earle Thompson. Not really. We weren’t friends. I learned about his death via email.

I was saddened, but I wasn’t surprised by his early death.

The last time I saw Earle, he was drunk.

He’d attended one of my poetry readings at the since-defunct Standard Books in Seattle, and after drunkenly heckling me, had traveled with us to the nearest restaurant.

I’d purposely picked a place that I knew didn’t serve alcohol.

For an hour or so, Earle sang and laughed at his own jokes and scribbled poems on napkins.

But he didn’t want to completely sober up, so he left us to our herbal teas and tasteless vegan muffins.

The first time I saw Earle, he was drunk.

In 1992, at the Returning the Gift Native American Writers Conference in Norman, Oklahoma, Earle was one of hundreds of eccentric and lonely and ambitious and hilarious and serious Indian writers.

But I spotted him instantly.

He was a small man and he smelled like salmon.

I don’t mean that he actually smelled like salmon. He metaphorically smelled of salmon. I knew, with all of my senses, including those mysterious and imaginary sixth, seventh, and eighth ones, that Earle was a salmon boy, just like me.

And after meeting him and reading his poems for the first time, I thought that Earle was destined for greatness.

He really was that good.

Take a look at his poems.

He was an incredible poet.

Better than every poet who teaches at the University of Washington.

Better than every poet who will be slamming this weekend at yet another Seattle open mic night.

Last year, when my wife read Earle’s Real Change poetry chapbook, she marveled.

“Who is that guy?” she asked.

“He’s Yakama,” I said.

And I told her the story about Earle and his first poetry chapbook, published by Blue Cloud Quarterly back in the early 1970s.

“I don’t know if this story is true or not,” I said. “But when people talk about Earle and his poetry, it’s the story they tell.”

After Earle received his contributor copies of his poetry chapbook, he celebrated by getting drunk at every bar on or near the Yakama Indian Reservation.

And, at every bar, he signed and gave away copies of his chapbook to friends, strangers, and any random passers-by.

He gave away all of his contributor’s copies.

All of them.

When he woke the next morning, he realized what he had done. He’d given away everything.

So he went back to the bars and found copies of his chapbook stuffed into garbage cans, toilets, and dumpsters. He found copies strewn across parking lots, dirt roads, and dance floors.

“That’s so sad,” my wife said. “It’s so Indian.”

Yes, Earle was so Indian.

He was an incredibly gifted poet who could not defeat the demons of alcoholism, racism, classism, mental illness, and colonialism.

On every reservation, in every tribe, there are dozens of Earle Thompsons, men and women of great talent, who fell apart, who disappeared, who died.

When one of them dies, all of them die. When we mourn any one of them, we mourn all of them.

We mourn the unrealized greatness.

We mourn our collective losses.

We are a defeated people. And we are always, always reminded of our failures.

“Do you think Earle will ever sober up?” my wife asked.

“No,” I said.

“He’s an incredible poet.”

“I know.”

“He’s better than you,” she said and laughed. She wanted me to think she was half-kidding, but she wasn’t. She really thinks that Earle is a better poet than me. I think so, too.

In a better world, Earle would have been a sober college professor and poet.

He would have been continually and constantly celebrated.

In this real world, Earle was mostly ignored.

But he should not be forgotten.

And I hope, through his poems, he remains immortal.

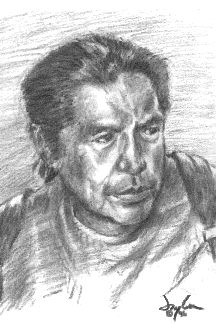

Sherman Alexie is a Coeur d’Alene Indian poet, writer, filmmaker who grew up on the Spokane Indian Reservation, and a member of the Real Change Advisory Board.